A Narrative Review of the Psychophysiological Effects and the Effects on Performance, Injuries and the Long-Term Adaptive Response.

Van Hooren, B., Peake, J.. Sports Medicine. 48, 2018.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-018-0916-2

It is widely believed that an active cool-down is more effective for promoting post-exercise recovery than a passive cool-down involving no activity. However, research on this topic has never been synthesized and it therefore remains largely unknown whether this belief is correct.

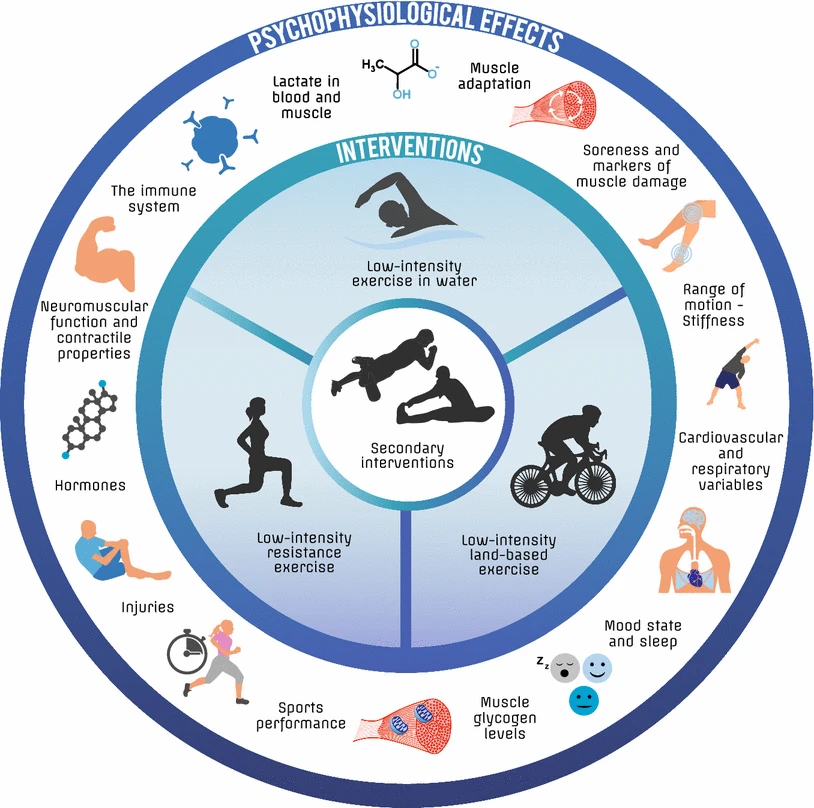

This review compares the effects of various types of active cool-downs with passive cool-downs on sports performance, injuries, long-term adaptive responses, and psychophysiological markers of post-exercise recovery.

The findings of this review will be of primary interest to athletes and practitioners who regularly use an active cool-down to facilitate recovery between training sessions or competitions, but are interested in what evidence exists that supports the use of an active cool-down compared with a passive cool-down.

What they did

The authors only included studies that have compared an active cool-down with a passive cool-down that consists of sitting, lying, or standing (without walking). They have also restricted the review to studies that have investigated the effects of performing an active cool-down within approximately 1 h after exercise, because findings from a recent survey suggest that this most closely replicates the cool-down procedure of many recreational and professional athletes. The primary focus is on how active cool-downs influence performance and psychophysiological variables during successive exercise sessions or competitions [i.e., approximately > 4 h after exercise, or during the next day(s)].

Relevant studies have been searched in the electronic databases of Google Scholar and Pubmed using combinations of keywords and Booleans that included (cool-down OR active recovery OR warm-down) AND (sports performance OR recover OR recovery OR physiological OR physiology OR psychological OR psychology OR injury OR injuries OR long-term adaptive response OR adaptation).

What they found

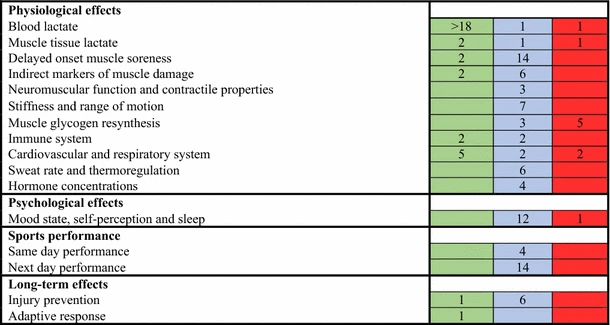

An active cool-down is largely ineffective with respect to enhancing same-day and next-day(s) sports performance, but some beneficial effects on next-day(s) performance have been reported. Active cool-downs do not appear to prevent injuries, and preliminary evidence suggests that performing an active cool-down on a regular basis does not attenuate the long-term adaptive response. Active cool-downs accelerate recovery of lactate in blood, but not necessarily in muscle tissue.

Performing active cool-downs may partially prevent immune system depression and promote faster recovery of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems. However, it is unknown whether this reduces the likelihood of post-exercise illnesses, syncope, and cardiovascular complications.

Most evidence indicates that active cool-downs do not significantly reduce muscle soreness, or improve the recovery of indirect markers of muscle damage, neuromuscular contractile properties, musculotendinous stiffness, range of motion, systemic hormonal concentrations, or measures of psychological recovery. It can also interfere with muscle glycogen resynthesis.

Practical takeaways

An active cool-down generally does not improve and may even negatively affect performance later during the same day when the time between successive training sessions or competitions is > 4 h. Similarly, an active cool-down has likely no substantial effects on next-day sports performance, but can potentially enhance next-day performance in some individuals.

With regard to the long-term effects, a cool-down likely does not prevent injuries, and preliminary evidence suggests that an active cool-down after every training session does not attenuate and may even enhance the long-term adaptive response.

If implemented, an active cool-down should:

(1) involve dynamic activities performed at a low to moderate metabolic intensity to increase blood flow, but prevent development of substantial additional fatigue;

(2) involve low to moderate mechanical impact to prevent the development of (additional) muscular damage and delayed-onset muscle soreness;

(3) be shorter than approximately 30 min to prevent substantial interference with glycogen resynthesis;

(4) involve exercise that is preferred by the individual athlete.

Cyrus’ Comments

The majority of the studies included in this review investigated the effects of an active cooldown on untrained or recreationally trained individuals so it would be beneficial to see further work on this topic include elite athletes to assess whether effect sizes increase or decrease in these groups.

Personally, despite the inconclusive findings of this review, if given the choice I would almost always prefer a short active recovery immediately post competition. The majority of races end in some kind of sprint or effort above maximal aerobic power, resulting in accumulation of blood lactate. This review indicates that an active recovery assists in the more rapid removal of this blood lactate so I’d see this as beneficial even just from a comfort perspective before jumping in the team bus for the transfer to the next race.

An active recovery is not always logistically possible with the location or timing of certain race finishes and sometimes for athletes a passive recovery is the only option. It’s therefore reassuring to see that a passive recovery in comparison does not negatively affect next day performance and the excess lactate will be cleared eventually regardless.

Want to know the optimal cool-down intensity for lactate removal? Read on here: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/765313/

This research article summary is one of many produced for semiprocycling.com in the monthly Cycling Science Digest. If you’re interested in articles like this and keeping up with the latest research as it is published then head over and subscribe to get the latest delivered to your inbox on the first of every month.

Until then, I’ll keep reading the research papers so you can spend more time on the bike.

Cheers,

Cyrus

Support the Site

More support from generous readers means more research shared with everyone! Feel free to request your own topic along with your donation via the contact form. Thanks!

A$10.00